Daine Singer

Melbourne

26 July–25 August

2012

Solo exhibition

About the exhibition

Essay by Simon Gregg

About

‘Ordinary Picture’ is a continuation of Alice Wormald’s investigation into the contemporary landscape through the use of image selection, manipulation and collage as a basis for her oil paintings and accompanying watercolours on paper. Her paintings mediate her relationship with and experience of space and nature through a controlled sense of photorealism, grounded in concerns around the act of painting and the physicality of paint itself. Using pictures from her collection of found imagery, nature photography and natural spaces, the works are infected by formal and conceptual concerns derived from art history and the abstraction of nature and landscape. While the paintings mimic the smoothness of the photographic surfaces from which they are derived, they vibrate with a visual conversation between scale, composition, colour and texture. The works effect a displacement through which the familiar appears strange, and are not concerned with narrative or meaning, but are a meditation on visual language and the space around us, the sublime, the magic and the majestic.

Essay

In ‘Occluded View’ Alice Wormald proposes a new kind of natural world, where the laws of gravity and scale have been thwarted, and the life that carpets the forest floor is flourishing unchecked. That her subjects are mostly small in scale, floral in nature, and excised from magazines is little comfort, for they lurch and leer at us in a most disconcerting manner.

Upon first encounter her works are disorienting but beguiling; small-scale plant specimens loom threateningly, their leaves and flower petals curling forward and seemingly beyond the picture surface. There is a spatial illusionism that has nothing to do with traditional perspective. Instead, there is a sense of layered flatness, with the depth achieved through the delineation of the edges of the forms. We move as though in a mythic landscape, where the lurid veils of petals and leaves may just vanish at the slightest touch or a shift of the glance. We find ourselves hypnotised, trying to compute the arrangement, but failing at every turn.

Wormald creates neither botanic illustration nor natural landscape, but instead a kind of florid utopia that has a greater debt to science fiction than anything found on earth. Like the triffids of John Wyndham’s book, the plants seem to creep across the surface of the picture as if in possession of independent intelligence; their mission to consume all that lives and breathes. We find ourselves at once repealing in horror and drawn helplessly closer. Each work blurs the division between the natural and the unnatural – indeed, Wormald has previously painted fake plants – and she constantly leads us to question the authenticity of what we see.

Wormald is also careful to exclude the presence of humans from her work, although the intervention of humans is palpably evident in the arrangements. Many of the works make further allusion to humankind, through the gentle folds of flesh-like foliage. We imagine beads of sweat and skin pores, and a certain lushness that is inherently feminine. There are other traditional indicators of the female present also, forming a mutant biology with the plant forms.

Wormald’s Occluded View began life in the depths of a subterranean cave. Earlier work concerned states of darkness, and its capacity to devour at will. With these new works she leads us back to the mouth of the cave, to the first incursion of organic growth. They retain, however, the chill of the dark; its heady moisture and its strange ambiguity. Emerging into clear view, the forms are no less pernicious than we had imagined them in the depths. Indeed, they remain completely unfathomable.

The traditional points of reference have become eroded, and we struggle to apprehend the new order in place. Wormald begins with montages of images drawn from a variety of sources. The images are carefully shifted and layered until they rest just so, perhaps in alignment with some unseen cosmic rhythm, before they progress to linen. This stage is signified by a spark of alchemy, by which the painting process invests the images with a strange and exotic exaggeration. The various elements cavort with darkness, and seem to be nourished by the dank undergrowth rather than the heavens above, which have themselves been consumed. The spaces become shallow and claustrophobic, with some sections undergoing a blurring. The relationship between fore, middle and background is ruptured so that we ‘read’ the picture as a series of lurid shapes pressing out at us. Unlike the panoramic landscape where we survey outward from a position of security, Wormald places us within and enclosed, to propose a kind of anti-panorama.

Each work achieves a penetrating disquiet through an upending of scale. Small objects in sharp focus are positioned behind larger objects that are blurred, so that spatial orientation becomes impossible. In spite of implying the edges of the cut paper Wormald overcomes the affectations of montage, to fathom instead a swirling, visceral world of amplified megaflora. The effect is somehow heightened by the source imagery, lifted from gardening magazines and plant books, which is innocuous in the extreme. That these harmless and dainty specimens should conspire to become so unearthly and dreamlike is particularly unnerving.

There is, we must not forget, an edge of defiant beauty that radiates from Alice Wormald’s pictures. Beauty was once a dirty word in art circles but today it blossoms freely, with the present works acting as exemplars of the resurgence. Importantly for Wormald, her beauty is laced with danger – it is not safe and domesticated as in the picturesque tradition, but becomes something altogether more sinister and sublime. We are afforded no secure vantage point, and must drift through each work quite at the will of the artist.

In so doing Wormald’s paintings become exercises in the psychological, rather than the physical. They reflect upon inner states – a kind of blissful delirium – through the means of everyday substance. They are baroque, extravagant and immersive, but also quiet, eerie and pensive. Alice Wormald’s unsettling hybrid of plant specimens reinvents the natural world anew, and helps us to locate a dreamy otherworld within the sinews of our everyday experience.

Simon Gregg

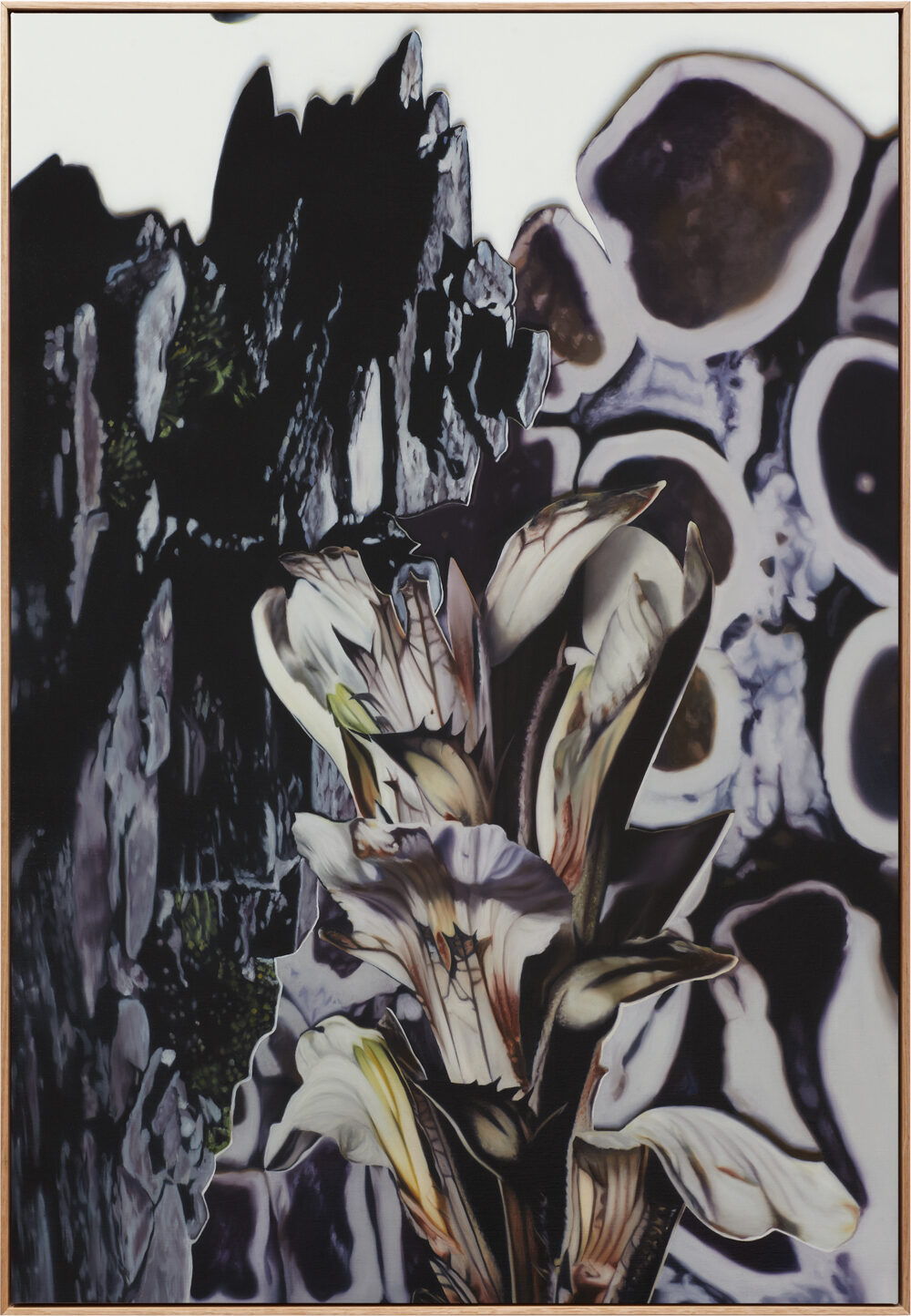

Untitled #5

2012

Oil on linen

112 × 76cm

Untitled #2

2012

Oil on linen

56 × 81cm

Untitled #1

2012

Oil on linen

56 × 81cm

Untitled #11

2012

Oil on linen

112 × 76cm

Untitled #4

2012

Oil on linen

56 × 81cm

Untitled #12

2012

Oil on linen

112 × 137cm

Untitled #6

2012

Oil on linen

112 × 76cm

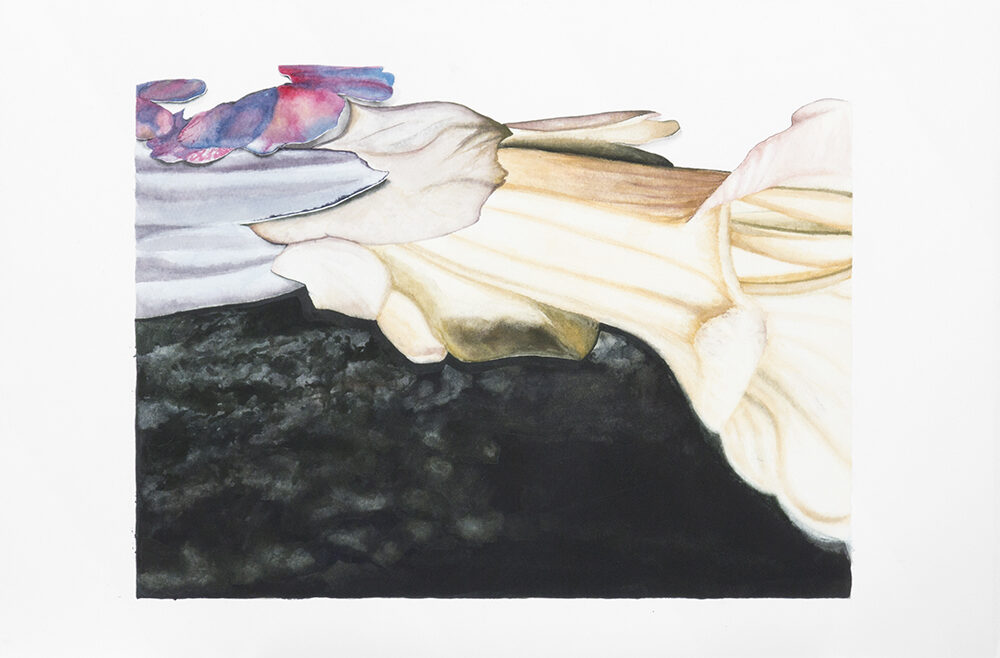

Untitled #14

2012

Watercolour on paper

38 × 56cm

Untitled #10

2012

Watercolour on paper

38 × 56cm

Untitled #13

2012

Watercolour on paper

38 × 56cm

Untitled #8

2012

Watercolour on paper

38 × 56cm

Untitled #5

2012

Oil on linen

112 × 76cm

Untitled #2

2012

Oil on linen

56 × 81cm

Untitled #1

2012

Oil on linen

56 × 81cm

Untitled #11

2012

Oil on linen

112 × 76cm

Untitled #4

2012

Oil on linen

56 × 81cm

Untitled #12

2012

Oil on linen

112 × 137cm

Untitled #6

2012

Oil on linen

112 × 76cm

Untitled #14

2012

Watercolour on paper

38 × 56cm

Untitled #10

2012

Watercolour on paper

38 × 56cm

Untitled #13

2012

Watercolour on paper

38 × 56cm

Untitled #8

2012

Watercolour on paper

38 × 56cm