Daine Singer

Melbourne

26 February–29 March

2014

Solo exhibition

Essay by Kelly Fliedner

Essay

‘We know, but cannot grasp, that above and below, beyond the limits of perception or imagination, thousands and millions of simultaneous transformations are at work, interlinked like

a musical score by mathematical counterpoint. It has been described as a symphony in geometry, but we lack the ears to hear it.’

– Stanislaw Lem, Solaris

Here Stanislaw Lem describes the encounter between planetary explorers from Earth and the sentient ocean planet Solaris. The planet is capable of awe-inspiring biological complexity, and chemical and environmental transformation, yet all attempts to form communication have failed. His novel of the same name ominously ruminates on the conditions and limits of human communication and knowledge, in the face of an uncharted universe.

Creating worlds—whether they be utopic or dystopic—is crucial to the sci-fi genre. Authors, like Lem, generally build fantastical worlds that intrigue, captivate and frighten readers who marvel upon the uncannily familiar results. There is something distinctively science fiction about Alice Wormald’s far from ordinary, Ordinary Pictures. The images are at once familiar and unknown—reflecting that sci-fi compulsion to make alternate environments and to build self contained worlds. Presented here is an array of landscape experiments that position Wormald as author, sole creator and giver of life to these strange, uncanny, spliced-together uninhabited scenes.

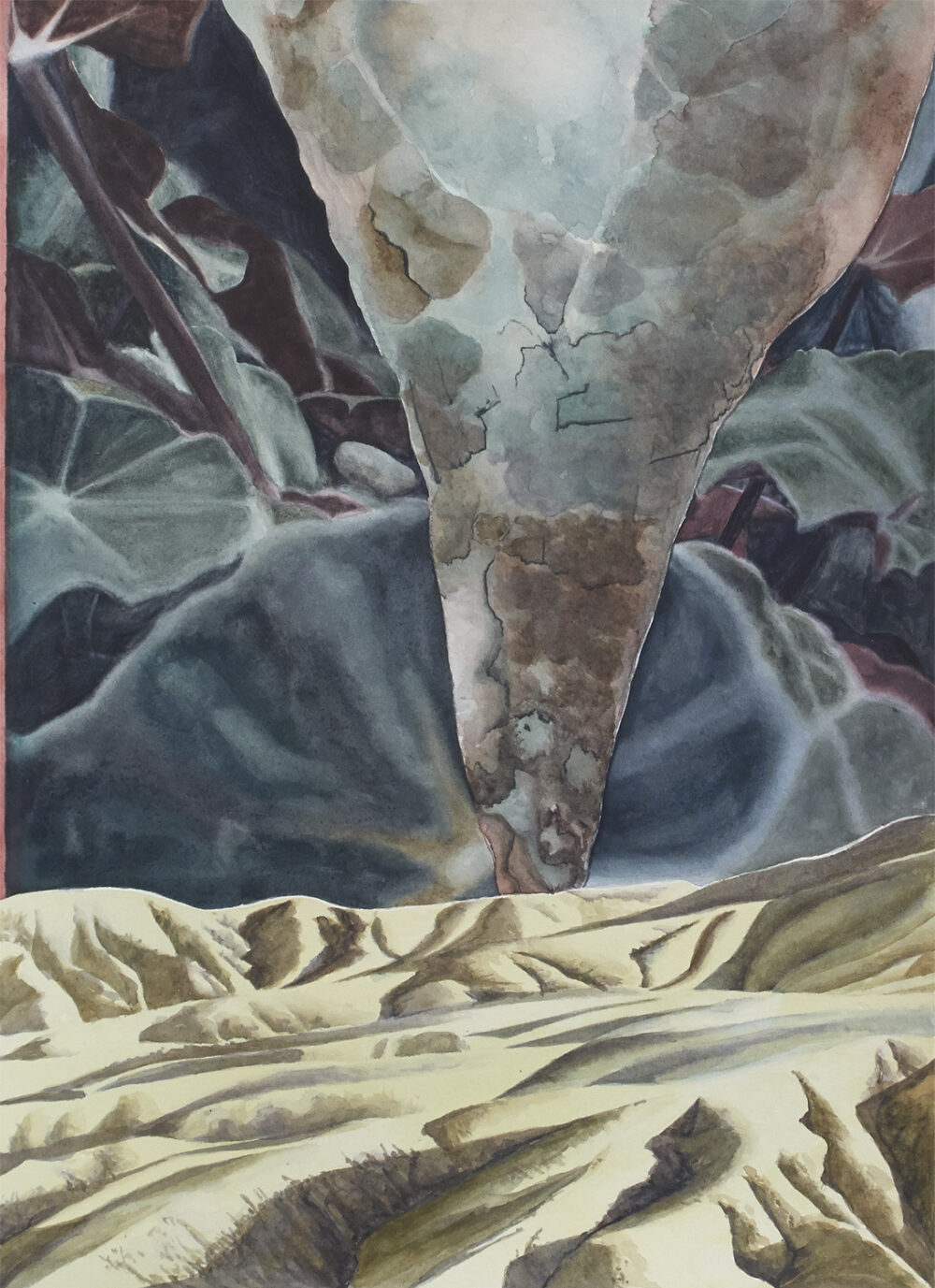

Wormald’s landscapes toy with perception and depth. The collapsed layers and collaged images of Water Garden are simultaneously independent from each other and intimately connected. The images are not necessarily a simplification of forms, space or light, they are rather a re-juxtaposition of elements within the whole. A black river winds its way through two discrete aerial views of arid desert, making its way to the burnt landscape above to become the river’s mouth—the layers bleed into each other.

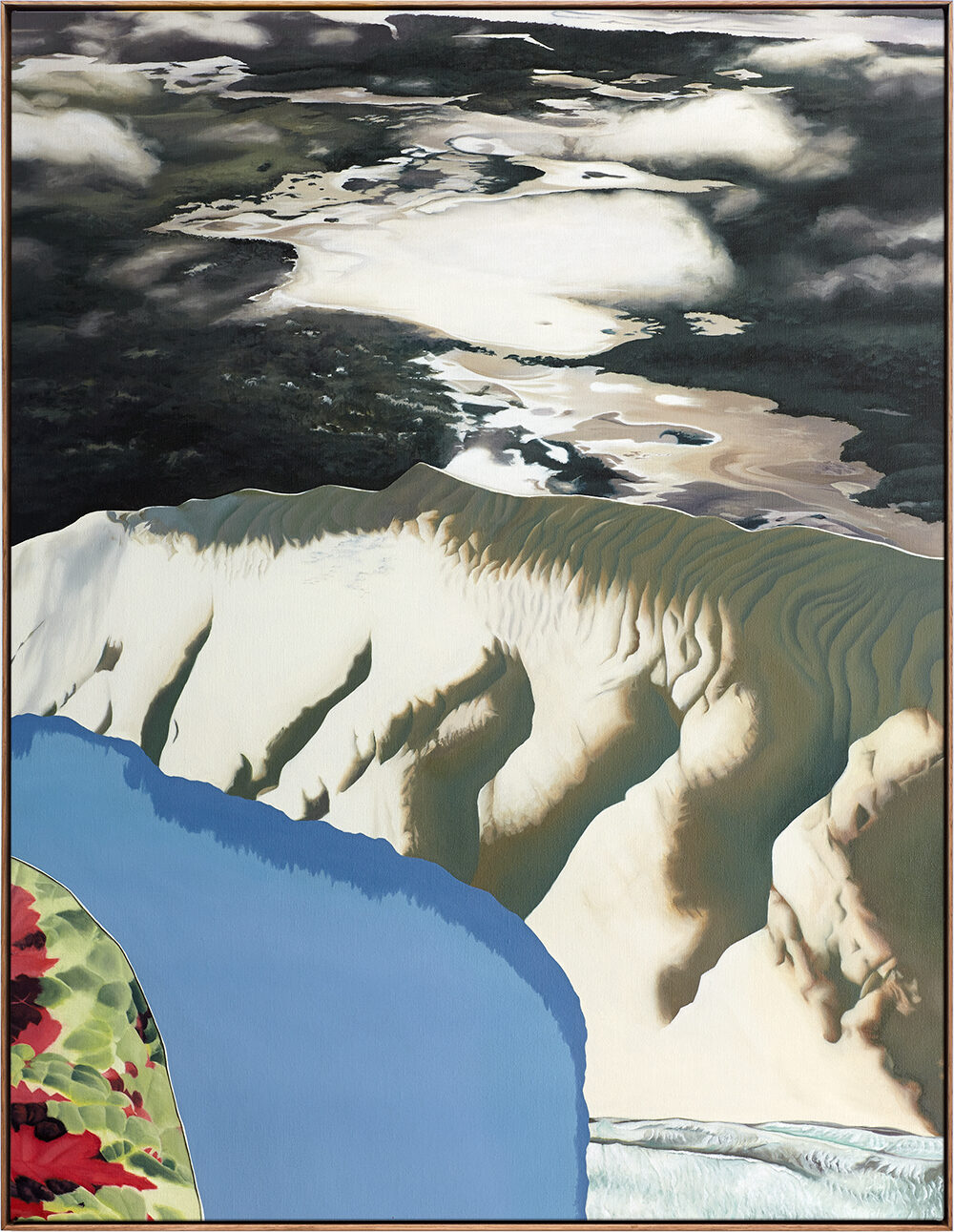

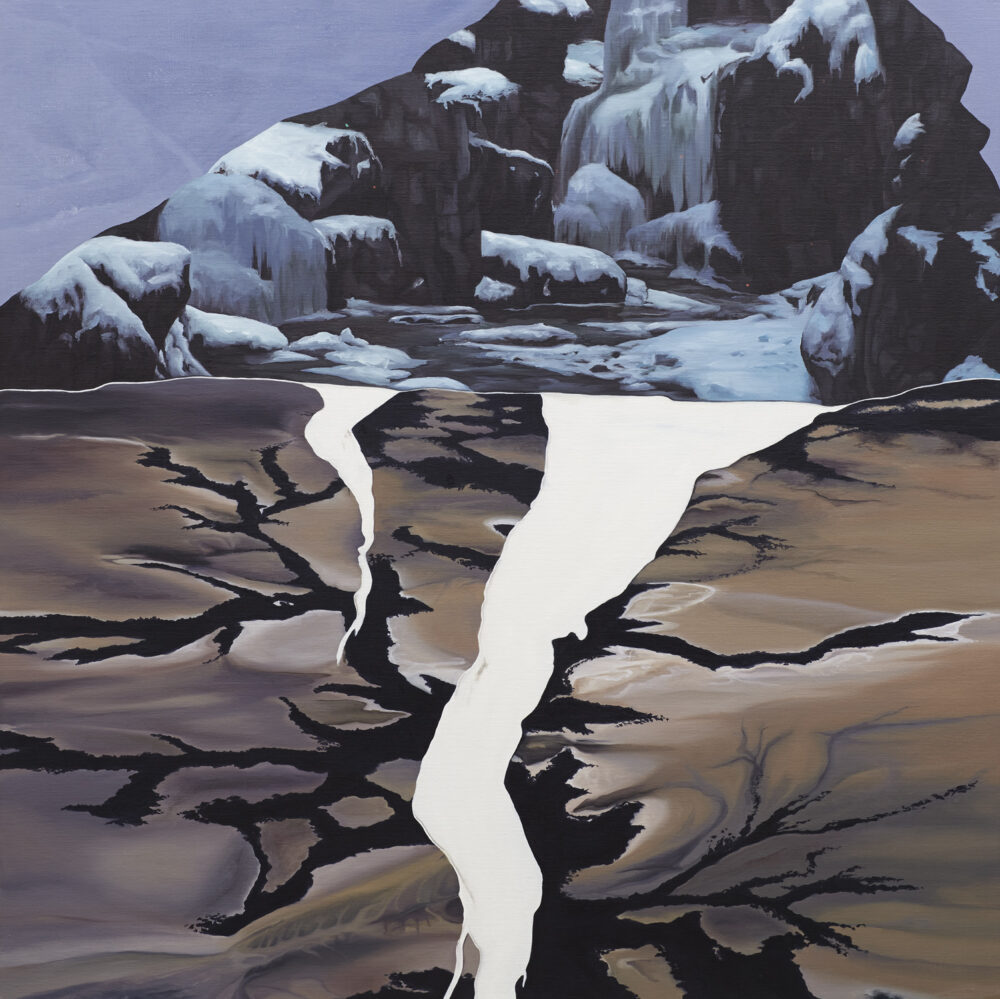

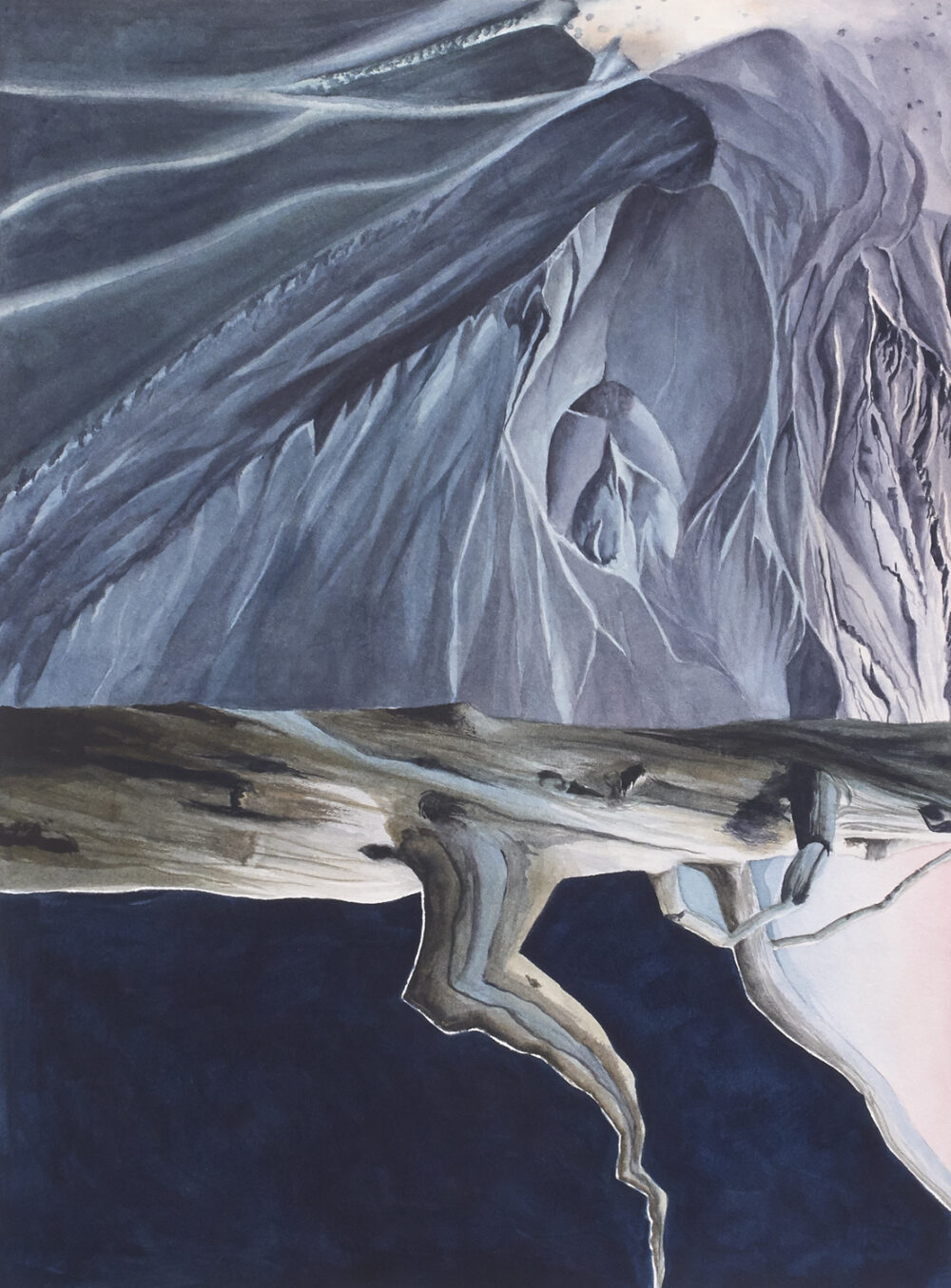

Wormald reinterprets the world and our environment, through abstract juxtapositions of the essential elements of form, colour and line. In Badland, four cross-sectioned landscapes with alternate perspectives are layered to present an environment at the limits of knowledge. Some shapes are identifiable as trees, mountains and ice (or perhaps stone), however the unnatural boundaries created through the collaged imagery compound the faults of our comprehension. If the notion of utopia is a place for the ideal then perhaps these strange environments form a space for the eerie dystopic sci-fi impossible.

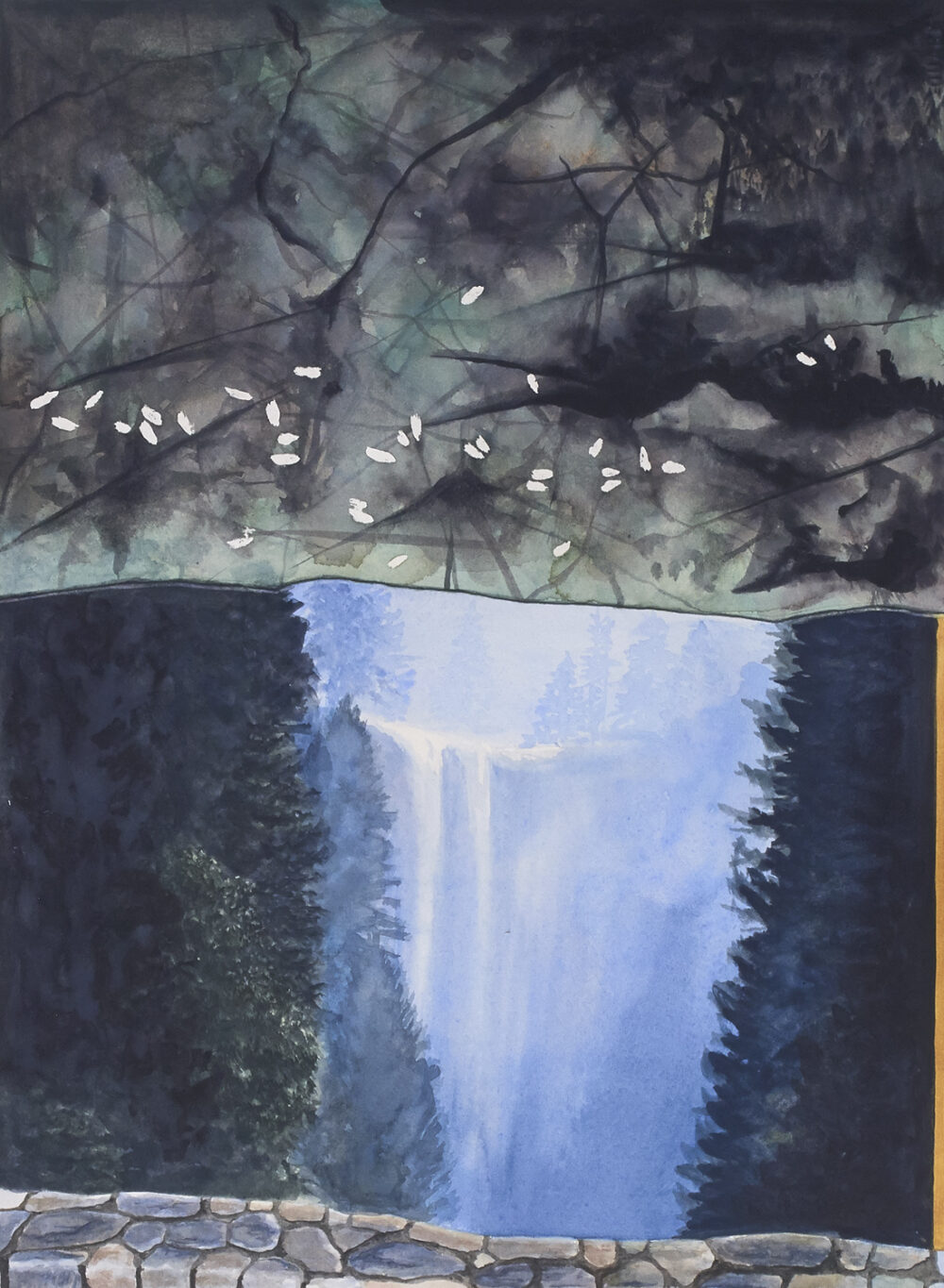

Wormald’s paintings mimic and forge the vertical perspective of Japanese landscape painting of receding up the image in portrait orientation, whilst actually not receding at all, rather each particular layer is squashed up against the next, such as in Reeds Japan. Most of the works have dispensed with the atmospheric perspective of creating large blank areas—which in Japanese paintings appear like clouds or mist. Instead here the foreground is divided from the middle ground, and the middle ground from background by contrasting layers of texture and recognisable indicators of distance from within the found imagery. Although at times this is difficult to comprehend.

For instance, in the eponymous work Ordinary Picture, quite obviously a tree stands in the foreground, but what it frames, what lies beyond it is difficult to grasp or make sense of spatially—is that a broken ice shelf, a snowy mountain range, foliage, a detail of the planet’s curvature, an image from space?

Many of Wormald’s works borrow from Japanese landscape gardening that develop intricate scenes within gardens by working with views outside. For instance, a hill or forest behind a garden is framed by trees planted within. In Wormald’s paintings these framing devices are emphasised by the revealed collage process of the paintings—the lines where images have been cut are clear and severe, and often supported by a shadow forcing particular layers further out of the frame. This continual investigation into modes of depth and composition and extreme overdoing of layers builds bazaar, lush and engrossing environments.

Borrowed Scenery evokes the iconic ghost-like landscapes of Georgia O’Keeffe’s New Mexico desert ranges filled with twisting trees, and omnipotent mountain ranges. As the

mother of American Modernism, O’Keeffe transformed the landscape around her into abstraction. Wormald’s painting is reminiscent of the bright palettes and flatness of O’Keeffe and her colour stacked environments presented as spacious and contemplative, as grand and utopic—suggestive of scenes from iconic Western American cinema.

Alternatively Wormald’s landscapes are presented as brooding and alluring non-places—an unforeseeable break has occurred between the elements within the painting. That background is too far away, that angle is wrong, is it an aerial or horizon line? These disjointed layers rupture a causable linear chain between each other, the scene that plays out in front of us is not of this world. Wormald has borrowed the flat layers of O’Keefe’s landscapes and shuffled them around. These collaged landscapes at once flatten the surface of the painting whilst creating depth, and finding space, mimicking the great picturesque and awe-inspiring sublime of Romanticism. The spaces that can not be predicted—they occasion a room for the impossible to take place, and they build themselves up, piece themselves together, from the architectural rubble of O’Keefe’s modernist utopia.

A dark humour emanates from these dystopic worlds—they are an unlikely bringing together of fragments that riff on boundaries and frontiers of perception through form and composition. Wormald’s works foreground the vivid, evocative and open ended quality of the romantic gesture, are deeply indebted to the aesthetics of the sublime and engross the abstract landscapes of modernism.

Borrowed Scenery

2013

Oil on linen

112 × 87cm

Badland

2014

Oil on linen

55 × 40cm

Ordinary Picture

2013

Oil on linen

87 × 112cm

Reeds Japan

2013

Oil on linen

87 × 87cm

Tour Garden

2014

Oil on linen

122 × 102cm

Grass Drawing

2013

Oil on linen

87 × 87cm

Water Garden

2014

Oil on linen

55 × 40cm

Blue

2014

Watercolour on paper

45 × 35cm

Rock Wall

2014

Watercolour on paper

45 × 35cm

Dune

2014

Watercolour on paper

45 × 35cm

Old Painting

2014

Watercolour on paper

45 × 35cm

Tree

2014

Watercolour on paper

45 × 35cm

Borrowed Scenery

2013

Oil on linen

112 × 87cm

Badland

2014

Oil on linen

55 × 40cm

Ordinary Picture

2013

Oil on linen

87 × 112cm

Reeds Japan

2013

Oil on linen

87 × 87cm

Tour Garden

2014

Oil on linen

122 × 102cm

Grass Drawing

2013

Oil on linen

87 × 87cm

Water Garden

2014

Oil on linen

55 × 40cm

Blue

2014

Watercolour on paper

45 × 35cm

Rock Wall

2014

Watercolour on paper

45 × 35cm

Dune

2014

Watercolour on paper

45 × 35cm

Old Painting

2014

Watercolour on paper

45 × 35cm

Tree

2014

Watercolour on paper

45 × 35cm